The Dynamic Quadranym Model (DQM)

The intersection of semantic categories and sensory-motor areas suggests a unified mechanism for processing action, perception, and meaning. How we position ourselves in the world directly shapes our thinking, language, and interpersonal orientation.

Lead-in

A significant evolution is reshaping how we understand language, cognition, and intelligence. Across philosophy, cognitive science, and AI, researchers are increasingly recognizing the need for robust systemic frameworks to complement—and in some cases, challenge—the limits of traditional reductionist approaches. This shift is more than theoretical; it is a social intervention. It calls for us to revise how we model meaning, not as fixed content but as emergent coherence shaped by embodied, contextual interaction. In this spirit, the Dynamic Quadranym Model (DQM), alongside thinkers like Gary Tomlinson and Elan Barenholtz, contributes to a growing consensus: orientation, not representation, is the key to understanding how systems relate, adapt, and respond meaningfully over time.

The DQM is a semantic framework designed to support both AI and human understanding by structuring language as a system of orientation rather than fixed interpretation. Its innovation lies in how it models meaning dynamically—measuring not just definitions, but spectral shifts between words and systems based on context, responsiveness, and directionality.

Unlike models that rely on surface-level association, the DQM distinguishes between two core types of context:

Situational context refers to external conditions—what is happening in a story, conversation, or environment.

Dynamical context models the organism itself—its internal alignment, ongoing orientation, and capacity to track coherence over time.

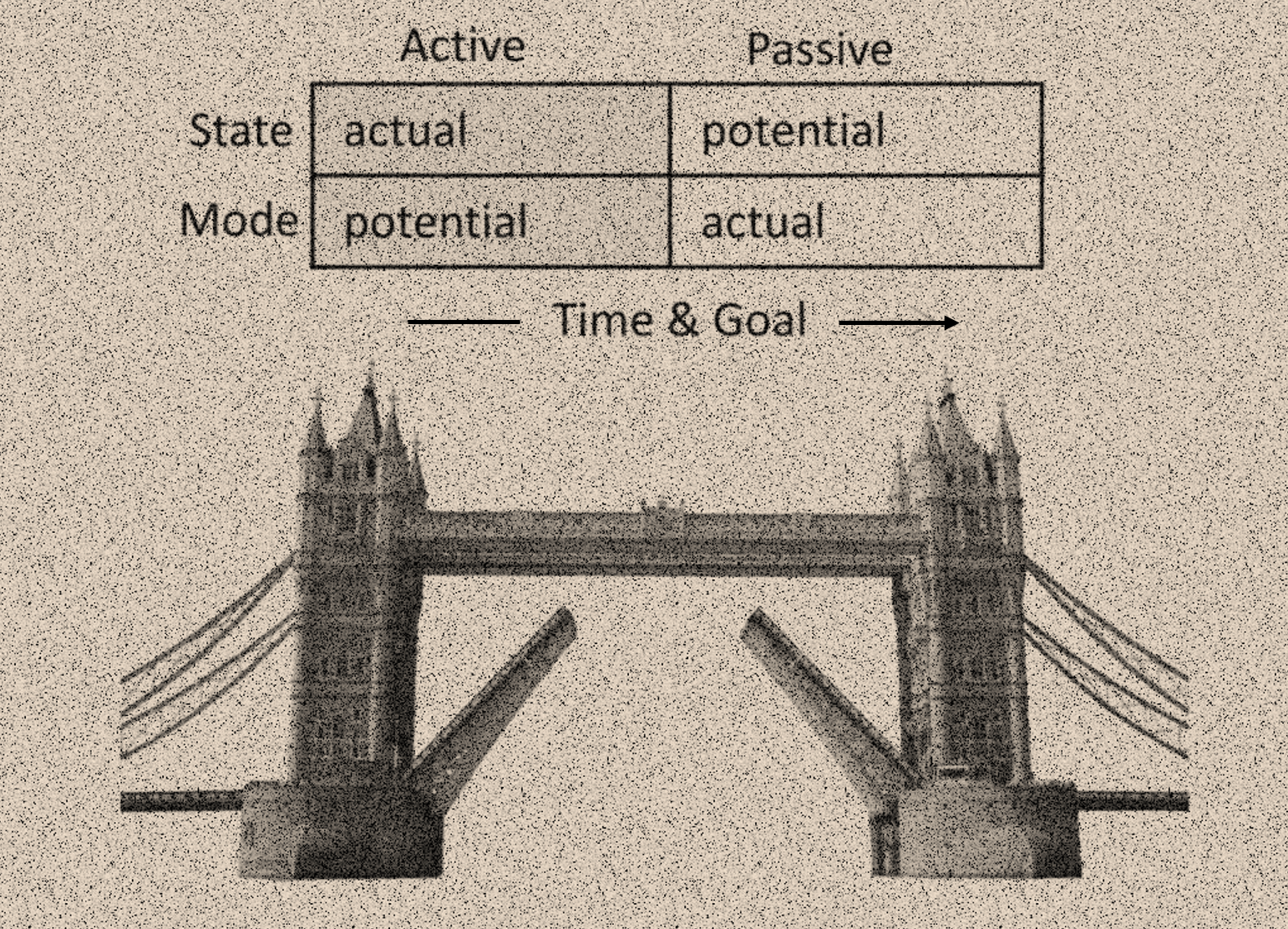

The DQM manages this through quadranyms. A quadranym is the smallest contextual unit in the model. It represents an agent’s orientational response—taking aim at a circumstance through latent standpoints and their target potentials. As the foundational unit, each interpretive segment of a text (situational context) is decomposed into its component tensions (dynamical context) using a faceted classification scheme. This begins with the prime quadranym classes: a four-part structure encoding subjective and objective state categories alongside expansive and reductive mode categories, offering a spatiotemporal snapshot of a responsive unit within the system’s ongoing flow. Each quadranym functions as a dynamic building block of orientation, guiding how meaning unfolds through interaction and time—within a broader system of quadranym units, scripts, and layers.

(See bottom of page for Dynamic Quadranym Model example.)*

Together, these orientational quadranyms allow the DQM to model not just what is said, but how an agent or system is meaningfully poised toward what is said. Quadranyms adjust, align and couple across hierarchical layers in distinct ways—a structure that helps AI produce responses that feel less like output and more like interpersonal engagement.

Orienting to Meaning

Orientation in the DQM is the process by which a system dynamically aligns with context—situationally, personally, and interpersonally. It integrates sensorimotor, linguistic, and conceptual dynamics to enable coherent responsiveness across layered experience. Acting as a B system to the LLM’s A system, the DQM enhances the LLM’s ability to situate, generalize, interpret metaphors, and track overarching themes in conversations and narratives—making context more coherent.

This article explores where the DQM fits within the broader landscape of language, cognition, and orientation—alongside influential perspectives from evolutionary musicology, cognitive science, and process philosophy. It traces a throughline from Gary Tomlinson’s account of music and human evolution, through Elan Barenholtz’s autoregressive model of language, and arrives at the DQM’s unique contribution: the Semantic Core. While aligned in part with embodied language cognition—especially in its emphasis on simulating sensorimotor experience—the Semantic Core offers a distinct model of coherence grounded in embodiment, unresolvedness, and temporal alignment. It is a theoretical construct capable of constituting its own grammar of orientation.

Tomlinson, Barenholtz, and the DQM: Beyond Language and Music

Tomlinson’s Evolutionary Musicology

Tomlinson sees the origins of music and language not as a linear evolution from one to the other, but as distinct and parallel outcomes of shared cognitive, social, and motor roots. Both emerge from grounding structures that evolved prior to fully articulate language—structures rooted in intersubjective behaviors, rhythmic gesturing, and coordinated affective expression. In this light, music may have achieved structural coherence earlier, emerging as a socially integrative force, while language required further time to develop its symbolic and referential capacities. These early behaviors were not abstract linguistic representations but operated through intercorporeal alignment and mutual prediction that prefigured later semantic systems. Music and language evolved distinct sensibilities.

Where language is symbolic, propositional, and referential, music is performative, affective, and non-symbolic. It does not represent in the way language does, yet it powerfully organizes experience, structures emotion, and synchronizes collective action—operating more proximally than distally.

Tomlinson posits that language’s capacity to adopt a remote or generalized view was not present from the outset. It emerges later through layered interactions among sensorimotor, affective, and social systems. From this perspective, articulate language leverages symbolic bootstrapping to extend orientation beyond the immediate, while music more fluidly and proximally anchors embodied alignment and emotional affect.

So, as Tomlinson makes clear, he rejects the notion that music is a kind of proto-language. Instead, both language and music are seen as separate outgrowths from an earlier technosocial substrate: shared attention, tool use, coordinated gesture, and social learning. These fundamental behaviors predate both systems and provide the platform for their emergence.

Tomlinson cites the practice of flintknapping—striking a stone core with a hammerstone to detach flakes, later shaped into tools. The image above evokes entrainment through attention and posture: the young hominin is not merely observing but synchronizing orientation with the elder’s actions. This illustrates pre-linguistic alignment—shared temporality, embodied rhythm, and intersubjectivity without symbolic exchange. For Tomlinson, this is a foundation of musicking. But it also clears the trees, preparing the ground for the agriculture of advanced language—a condition in which speaking can take root, systematize, and flourish

Tomlinson’s account is deeply informed by the work of Michael Tomasello, whose theory of shared intentionality emphasizes the uniquely advanced human capacity for collaborative, socially structured cognition—building on comparative studies that show coordinated behavior in other primates. Tomasello rejects the idea of a dedicated “language instinct,” instead arguing that language arises from broader socio-cognitive abilities like joint attention, imitation, and cultural learning. This focus on the coordination of intention and perception aligns closely with Tomlinson’s view of music and language as parallel outcomes of embodied, interactive behavior. Both accounts underscore the idea that meaning-making begins not with symbols, but with the capacity to align with others in a shared orientation.

Barenholtz and the Autoregressive Language System

In contrast, Elan Barenholtz frames language as a self-contained autoregressive system—an internal engine that predicts and constructs its own semantic output through sequential learning. Drawing on analogies with large language models, he shows how language can function syntactically and statistically, generating coherent sequences without grounding in sensorimotor experience or world reference. However, Barenholtz does not claim that this system produces understanding. On the contrary, he highlights the gap: language, when treated autoregressively, can operate independently of meaning—even while giving the illusion of sense. This perspective underscores the need for something beyond language to account for coherence and relevance. It opens the door to a broader account of orientation—one that the DQM models and explores.

The Semantic Core as Orientation Engine

This tension—between Tomlinson’s embodied social flow and Barenholtz’s internal linguistic recursion—reveals a missing piece. Neither account aims to describe explicitly how systems like language and music are dynamically coordinated in real time—only that they are. Here, the Dynamic Quadranym Model introduces what both theorists point to but neither explicitly names: a procedural engine of orientation that we will call the semantic core. It is the site where coherence is actively sustained across divergent systems—where inputs from language, music, perception, and action are not fused, but related. However, caution is warranted. Before naming something like this, we ought to understand what it truly is. We can’t claim that we do—but it implicates a grammar, and that’s a promising start.

Before Meaning: The Grammar of Orientation

The Semantic Core isn’t a new discovery or localized structure—it’s a way of thinking about how a system actively orients toward meaning. It serves as a hypothetical construct for the grammar of orientation.

The Semantic Core is not semantic in the narrow linguistic sense (i.e., propositional reference), but in the broader, indexical sense of experience and relevance. It is the dynamic center of the system—where orientations form, tensions are resolved, and coherence is continually sought.

The Active–Passive Cycle in DQM

In DQM theory, the Semantic Core is active—meaning it requires work. It isn’t a passive processor of input but a system of effortful alignment, constantly interpreting incoming streams from language, music, perception, and motor-sensory systems. What it produces are orientational outputs: responses that may appear as words, gestures, musical expressions, or movements. But all of these emerge from the same underlying engine of coherence. Because this engine is active, it draws energy and incurs cost. That implies the Semantic Core must operate with some form of economy—choosing among responses, adjusting its intensity, and conserving resources while still maintaining meaningful alignment.

Fundamentally procedural, sequences initiate active sense that is confirmed by passive sense—like stepping (active) and then feeling the ground (passive), which completes the arc. Orientation is enacted between these two states and serves as a foundation for anticipating future situations. What is recalled is not just the passive state, but the entire cycle from active to passive, implying a procedural rather than semantic mode of recall. These cycles operate across hierarchical layers within the system, optimizing how each layer aligns and integrates these sequences.

Finding semantic consistency between active-actual and passive-potential categories is key to DQM’s efficiency—for example:

Agent: [(active(actual({self}))) → (passive(potential({goal})))]

Agent orientation between active and passive states casts self as stable reference and goal as shifting variable. While self remains conceptually constant, goal adjusts to situational demands. The passive state implies a system distinct from the agent’s active drive, creating a temporal and structural gap the Semantic Core must bridge through alignment.

As in the stepping example, the ground is not just a surface—it is a system: ground, earth, and gravity. Likewise, goal is not a simple object but a system composed of objects, plans, and desires. These systems provide the situational context to which active orientation must couple and align.

Here, the DQM makes a key distinction:

- Passive systems are those the Semantic Core can orient with—they provide inputs or structures to be used (e.g., language, music, others).

- Active orientation is what the Semantic Core does—it initiates, tests, and sustains trajectories of coherence amid competing constraints.

An active–passive cycle represents how orientation transitions from engagement to resolution, completing a meaningful arc. The active phase launches an action or intent; the passive phase concludes it, rendering the moment tangible and salient for the agent. This isn’t about objects being active or passive, but about how orientations close arcs. It is a recursive process that aligns active-passive states in a trajectory of coherence.

Division of Labor

Passive system provides active system opportunity for economy

So, passive systems are not necessarily inert—they range from non-autonomous tools, like a hammer, to autonomous systems like language. While such systems can operate on their own, they can also be actively taken up and redirected. Language and music provide continuous flows of patterned structure that the Semantic Core can entrain to and repurpose—drawing from them without needing to generate them. As Barenholtz shows, we engage language’s predictive dynamics through active orientation: realigning to restore coherence. Only through this personal coherence does the opportunity for interpersonal alignment emerge.

A Model of Embodied Analogs

This view of the Semantic Core builds on a lineage of thinkers who have emphasized the embodied and grounded nature of conceptual processing. George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, in their theory of conceptual metaphor, argue that abstract concepts are structured through embodied experience and metaphorical projection. Lawrence Barsalou’s research on perceptual symbol systems shows that conceptual understanding draws on sensorimotor simulations, not amodal symbols. Arthur Glenberg, tackling the symbol grounding problem, maintains that meaning emerges through embodied enactment, not abstract representation. And Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a foundational figure in phenomenology, reminds us that the body is not a vessel for thought but the very condition of it—an active participant in the shaping of sense. In this view, the body becomes its own analog—simultaneously grounding, guiding and extending orientation.

This process builds on the embodied language hypothesis shared by many cognitive scientists—that action, perception, and semantics are supported by overlapping neural systems. The DQM incorporates this view but extends it through James Gibson’s ecological psychology, where perception is not passive input but active engagement with affordances: possibilities for action that emerge through agent-environment coupling. In this framework, subjective and objective are mutually defined in relation. The Semantic Core is not confined to a brain region but emerges as a virtual, procedural structure—an alignment of brain, body, and environment unfolding across trajectories of action and attention. It becomes identifiable especially in moments of disruption, where coherence is not given but enacted—revealed through the effort to restore orientation.

While the Dynamic Quadranym Model (DQM) formalizes an orientation grammar for sustaining coherence, its semantic core functions as a heuristic—a conceptual anchor for the effortful, generative source behind semantic sensibility. Though not empirically localized, it remains a guiding principle for understanding the dynamic nature of orientation.

Music and Language: Not Merged, but Co-Processed

As was discussed, music and language do not flow from each other. Instead, they flow in parallel, often interacting but never fundamentally merging. Their connection is not structural but orientational—they are made to seem connected because the Semantic Core continuously organizes them into a shared flow of experience.

This explains why lyrics that prioritize flow, rhythm, and affect (e.g., Jon Anderson or Van Dyke Parks) often resist propositional analysis. The language system alone can’t predict them well, but the Semantic Core can still orient to them, using rhythm, rhyme, and embodied resonance as anchors of coherence. In this way, even chance associations can become meaningfully felt.

This orientational coherence often relies on entrainment—the temporal alignment of perception and action across systems. Music, in particular, provides rhythmic structures that the Semantic Core can entrain to, allowing it to stabilize meaning across bodily, emotional, and linguistic inputs. Even in language, patterns of prosody and pacing offer micro-entrainment opportunities that help the system stay in step with unfolding context. Orientation, then, is not only semantic but rhythmic—coherence is something we quite literally fall into together, by the nature of its effort.

The Trick of Music

Thus, music is a passive input—but a rich and dynamic one. Simulation amplifies it because it shares systems with motor action, perception, and affect. Yet the Semantic Core must still work with it to produce coherence. This is the source of the “trick”: music feels participatory, embodied, and agentive, even though it remains an input to the deeper orientational process.

The Effort of Motivation

When an baby bobs to music, it’s not passive—it’s the Semantic Core working to entrain with rhythm, driven by an energetic, coherence-seeking orientation that incurs real effort, even as the desire to participate remains—a responsive alignment with sensory streams.

The DQM’s Contribution

Where Tomlinson offers a positive case for the emergence of orientation through music, and Barenholtz argues for removing language from orientation itself, the DQM steps in to provide a grammar of orientation—one that elucidates how coherence arises across time and systems.

It defines orientation as the process by which active states (subjective engagements) relate to passive structures (objective conditions), using a bifurcated grammar of states and modes as semantic categories. The Semantic Core is where this happens—not as a place, but as a commitment: an organism’s inescapable drive to relate, adapt, and stay coherent.

The Semantic Core is semantic not because it defines propositions, but because it indexes experience—from linguistic cues, musical rhythms, bodily sensations, or abstract goals. It does so through simulation, relational closure, and dynamic enactment. It is where orientation becomes possible—even when the systems involved appear unrelated in their passive form. Active orientation is not driven by attention, but by procedural necessity—it initiates, modulates, and sustains coherence through top-down and bottom-up flows. It functions whether or not the process is consciously attended, operating as the underlying dynamic that holds disparate systems in coordinated alignment.

Beyond Sense-Making

In DQM, orientation is not sense-making. Sense-making may result from orientation, but orientation is the procedural, structural activity—prior to semantic resolution.

Tomlinson helps us feel the evolutionary need for such a system. Barenholtz helps us see what language cannot do on its own. And the DQM provides a coherent model for how everything—music, language, and beyond—can be processed without forcing unity where none exists.

So, orientation is not the product of either system, but the function that holds them in tension—without collapse. The DQM reveals this tension not as a flaw or a strain caused by an ad hoc attempt at unity, but as the condition under which orientation toward meaning becomes possible.

Afterword: Temporal Orientation, Consciousness, and the Promise of Process Thought

(Next Section Illustrates Key Components of DQM’s Grammar of Orientation.)

The Active-Passive Cycle

Clarifying the Quadranym Frame

Q Unit: Local Resolution

-

State: S (Subjective origin): Source (actual e.g., passage)

-

State: O (Objective intersection): Target (potential e.g., barrier)

-

Mode: X (Reductive mode): Independent (actual e.g., close)

-

Mode: Y (Expansive mode): Dependent (potential e.g., open)

The Q Unit resolves tension at a moment (temporal snapshot).

The Hyper Q tracks how these moments unfold across arcs.

A Q Unit, or standard quadranym, is tracked along the flow path as a point on the Hyper Q plot line the system zooms in on. While the Hyper Q offers a zoomed-out view—modeling large-scale conflations between poles along the Y-axis—the Q Unit bifurcates that spectrum, defining its own X and Y axes. This localized bifurcation adds another degree of freedom for managing conflations and enables a more agile, context-sensitive response.

Spatial Frame Reference: Higher-Level Nesting

Quadranym: Space[(actual(void)) → (potential(between))]

In this structure:

-

Void functions as the spatial background (a figure-ground relation).

-

Between marks divisions—regions, thresholds, solid separations.

The door quadranym nests under this, inheriting orientational coherence from void → between by anchoring on passage → barrier. In this way, a door may grant access to a jar or quick entry to a village through a valley. Each instance forms an active-passive cycle, a semantic orientation enabling economy and coherence.

This is possible because anchors like void or passage possess displacement power—they shift across contexts (e.g., door, storm, argument) yet retain their orientational function.

Formally:OFA(A) ≈ OFA(A₍Cₖ, Iⱼ₎)

Where:

-

A is the anchor (e.g., void, passage)

-

OFA(A) is its Orientational Functional Attribute—the core role it plays in guiding orientation

-

Cₖ is the context

-

Iⱼ is the specific instantiation within that context

The anchor’s role stays intact—even as its form or setting changes. It remains whole—semantically stable, even when dynamically repositioned. This enables recursive coherence across the orientation system.

Recursive Structure (Q Unit: Q<sub> T</sub>(A):[X → Y] ⇒ B):

For the anchor A of topic T, Potential (Y) is dependent on Actual (X) to find Objective state B.

Examples:

For the anchor void of Space, infinite is dependent on finite to find the objective intersection: between.

For the anchor passage of Door, open is dependent on close to find the objective intersection: barrier.

State Orientation: Nesting Scripts

Zoom-in Function:

DQM acts as the B brain to the LLM’s A brain for a more situated AI.

LLMs = Predictive Flow

DQM = Orientational Coherence

LLMs guess next words.

DQM tracks how coherence is disrupted and restored.

Together, they form a complementary architecture:

-

LLMs provide statistical prediction

-

DQM provides orientational logic

-

The Semantic Core relates both through dynamic feedback

The DQM doesn’t predict the next word—it predicts the next necessary orientation. Conflation functions as dynamic clustering based on semantic compatibility, not surface form. What matters is not the next token in a sentence, but what sustains the system’s orientational integrity.

The Takeaway

The “door” example demonstrates how the DQM generalizes orientation beyond content or reference. It showcases scalability by revealing the fundamental function of a quadranym: tracking the system’s capacity to reorient—not what a concept is, but what a concept does.

It does so through:

-

Layered structure (Q Unit, Hyper Q)

-

Consistent standpoint anchoring (e.g., passage)

-

Scriptable transitions (state & mode)

-

Feedback-driven coherence restoration

Meaning is not merely understood—it is enacted through orientation.