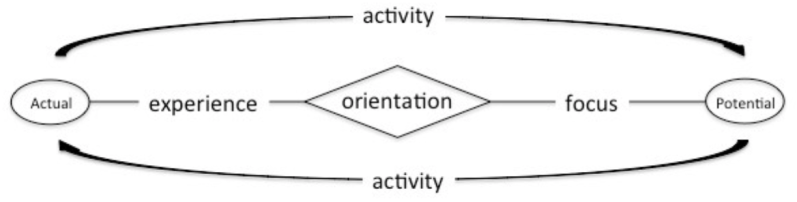

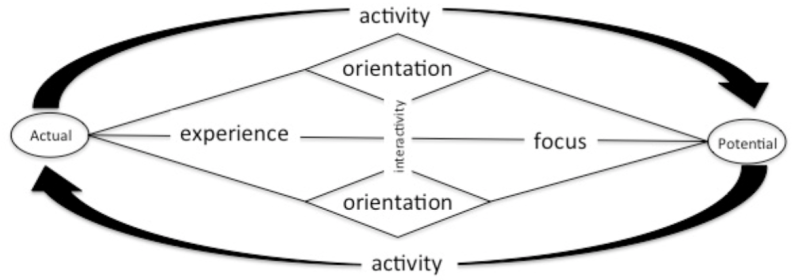

Achieving generalization—the ability to adapt language understanding across diverse contexts—is a core challenge in AI. Generalization enables commonsense and metaphoric reasoning, allowing systems to recognize patterns flexibly. The Dynamic Quadranym Model (DQM) within the Q model framework addresses this by structuring word embeddings to enable nuanced, adaptable interpretations. Through Word-Sensibility, Responsiveness, and Contextual Adaptability, DQM helps AI shift between literal and abstract meanings while conserving patterns for new contexts. A key method in DQM is to organize context-sensitive word associations along the X and Y axes, a process we call bifurcation.

To demonstrate this, we’ll explore scenarios where orientation analysis reveals how context shapes meaning, grounding DQM’s bifurcation models and topic traces for relating topics, as tools for commonsense adaptability. By incorporating a virtual dynamic sense—a context-free sense of change that actively seeks context—DQM aligns responsively as meaning shifts, enhancing AI’s flexibility and generalization. To illustrate DQM’s approach, we begin with two scenarios, each demonstrating orientation analysis:

Personal Orientation

Keys Story: The morning light streamed through the kitchen window, Sarah frantically searched for her keys, her heart racing with each passing minute. She rifled through the clutter on the kitchen counter, glancing at the clock, then dashed into the living room, where the cushions lay askew from last night’s movie marathon. “Where could they be?” she muttered, moving to the hallway, peering under the shoes and bags that seemed to have multiplied overnight. The bathroom was next, where she opened drawers filled with half-used toiletries, but all she found were loose change and forgotten receipts. With a sigh, she retraced her steps, her mind racing through the last places she’d been, determined to find the elusive keys before she was late.

Interpersonal Orientation

Eat Story: Two friends, Sarah and Tom, are looking for a place to eat after a long day exploring the city. They’re both craving something delicious but have different ideas on what that might be. Sarah leans toward a cozy, quiet spot with comforting food, while Tom wants something lively with bold flavors. They pull out their phones, scrolling through options, sharing ideas back and forth. After a bit of debating, they agree to try a bustling little bistro nearby that offers a mix of both their favorites—calm ambiance with an exciting menu, perfect for a relaxing meal together.

Traditional NLP vs. Orientation Analysis

In AI, traditional text analysis parallels methods in natural language processing (NLP), where techniques like sentiment analysis, topic modeling, and entity recognition aim to extract structured information from unstructured text. These NLP approaches, much like qualitative text analysis, categorize content based on predefined patterns, offering insights that are largely static and context-independent. While effective for labeling or summarizing, NLP lacks the adaptive generalization needed to shift meanings fluidly across contexts. By contrast, orientation analysis within the Dynamic Quadranym Model (DQM) fosters generalization, dynamically interpreting terms along DQM’s X-Y axes, such as proximity and remoteness (spatial dynamic sense), as contexts evolve. This enables DQM to support a deeper, context-sensitive understanding, moving beyond fixed categories to enable responsive, commonsense reasoning in AI.

Orientation Analysis Clarification: Orientation analysis doesn’t aim to replace traditional text analysis (TTA) but to supplement it by situating terms within evolving contexts. This coupling of dynamic orientation (dynamical context) with the situation (situational context) allows DQM to align meaning fluidly with context, enabling AI to interpret subtle shifts and adapt its understanding in real-time, creating a responsive layer that static NLP methods lack. A hybrid analysis (i.e., system layers) is the aim.

System Layers:

- Situational Context (TTA):

- Defines the immediate setting and relevance.

- Dynamical Context (DQM):

- Adjusts meaning through adaptive orientation.

Orientation analysis is primarily a focus on dynamical not situational contexts. The DQM framework might best viewed as a “B system” complementing the “A system” of large language models (LLMs).

• DQM’s orientation adds a private, dynamical context layer, enhancing traditional text analysis centered on public, situational and dynamic context.

DQM Hybrid vs. Traditional AI Systems

| Feature | Traditional AI | DQM Hybrid System |

|---|---|---|

| Static Knowledge | Relies on fixed, pre-trained patterns. | Builds on static patterns but reinterprets them dynamically. |

| Context Sensitivity | Limited adaptability to context shifts. | Dynamically adjusts meaning based on real-time feedback. |

| Transparency | Opaque neural layers. | Transparent quadranyms reveal orientation shifts. |

| Dynamic Coupling | Isolated word processing. | Words interact dynamically within an interdependent network. |

| Exaggerations/Metaphors | Pattern-based approximation. | Dynamically extends or reinterprets meanings. |

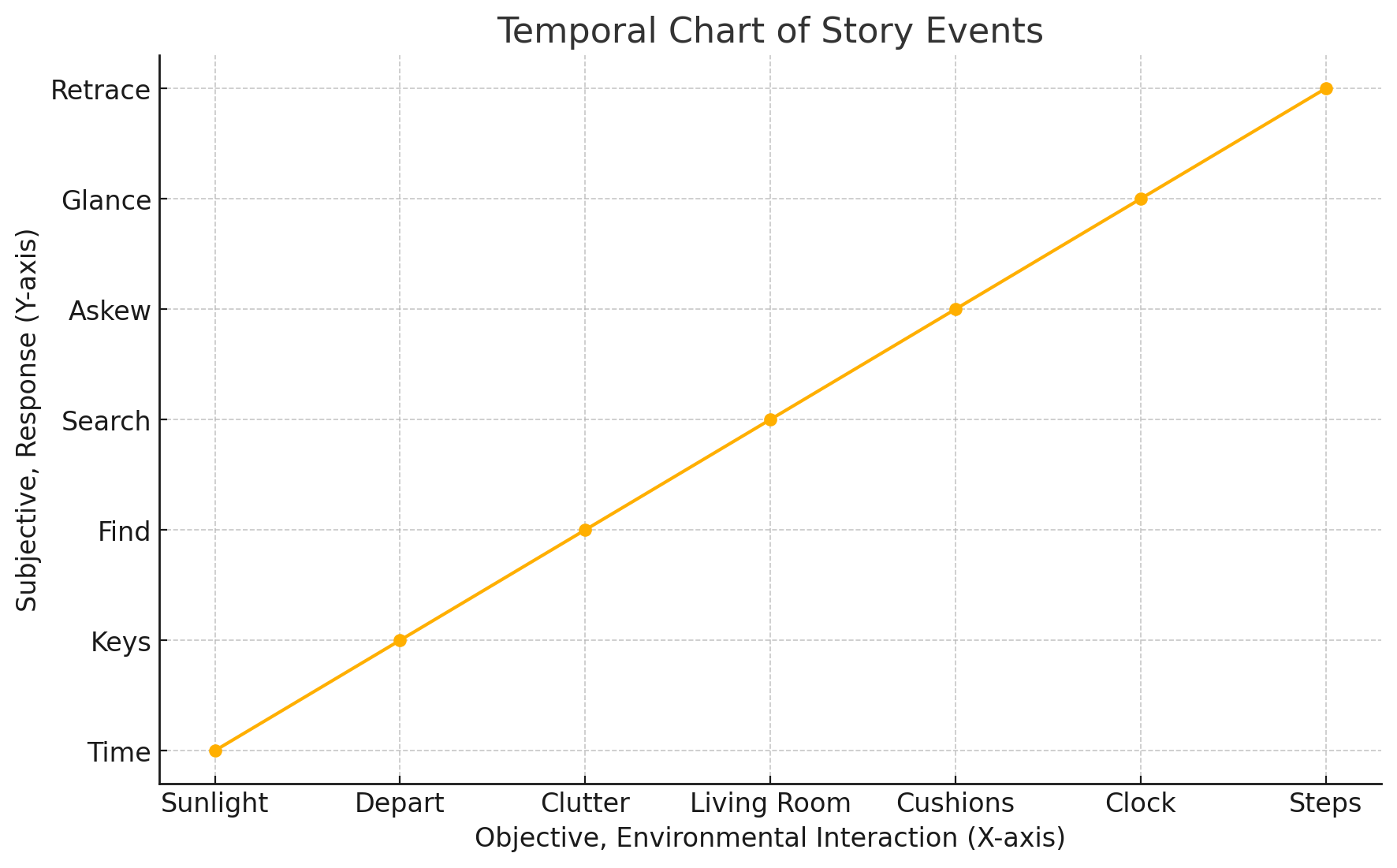

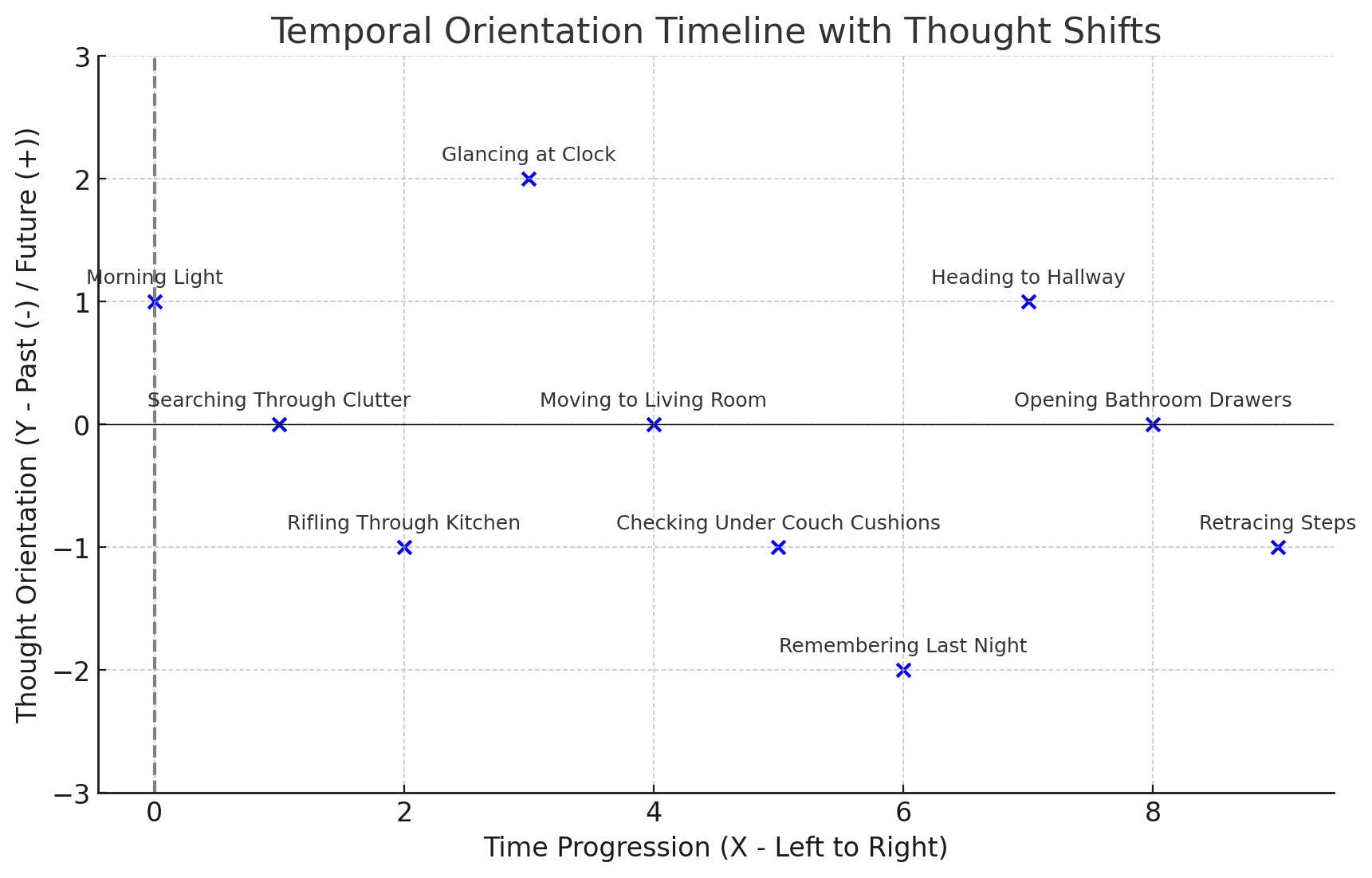

Summary of Personal Orientation Points in Correlation with Chart

- Setting Context: Morning light (Y-axis) frames time, while the kitchen window (X-axis) initiates her search.

- Execute Plan: Leaving the premises requires keys in possession.

- Escalating Urgency: As time ticks down (Y-axis), urgency rises, with the counter and living room (X-axis) anchoring her close proximities.

- Shifting Focus: The hallway and bathroom (X-axis) reflect a broader search as Sarah adapts.

- Building Tension: Unrelated items (X-axis) shoes and bags fuel frustration, while retracing steps (Y-axis) heightens urgency

In this orientation, proximity entails in reach; remoteness entails out of reach.

This adaptive framework within DQM captures immediate and broader orientations in Sarah’s search, dynamically shifting relevance in response to context. This interplay of proximity and remoteness sets up DQM’s goals, guiding how its embeddings achieve responsive, commonsense reasoning.

• DQM captures Sarah’s adaptive search by mapping urgency along the Y axis (remoteness) and proximity shifts along the X axis, dynamically framing “keys” as the goal amidst escalating urgency and spatial adjustments.

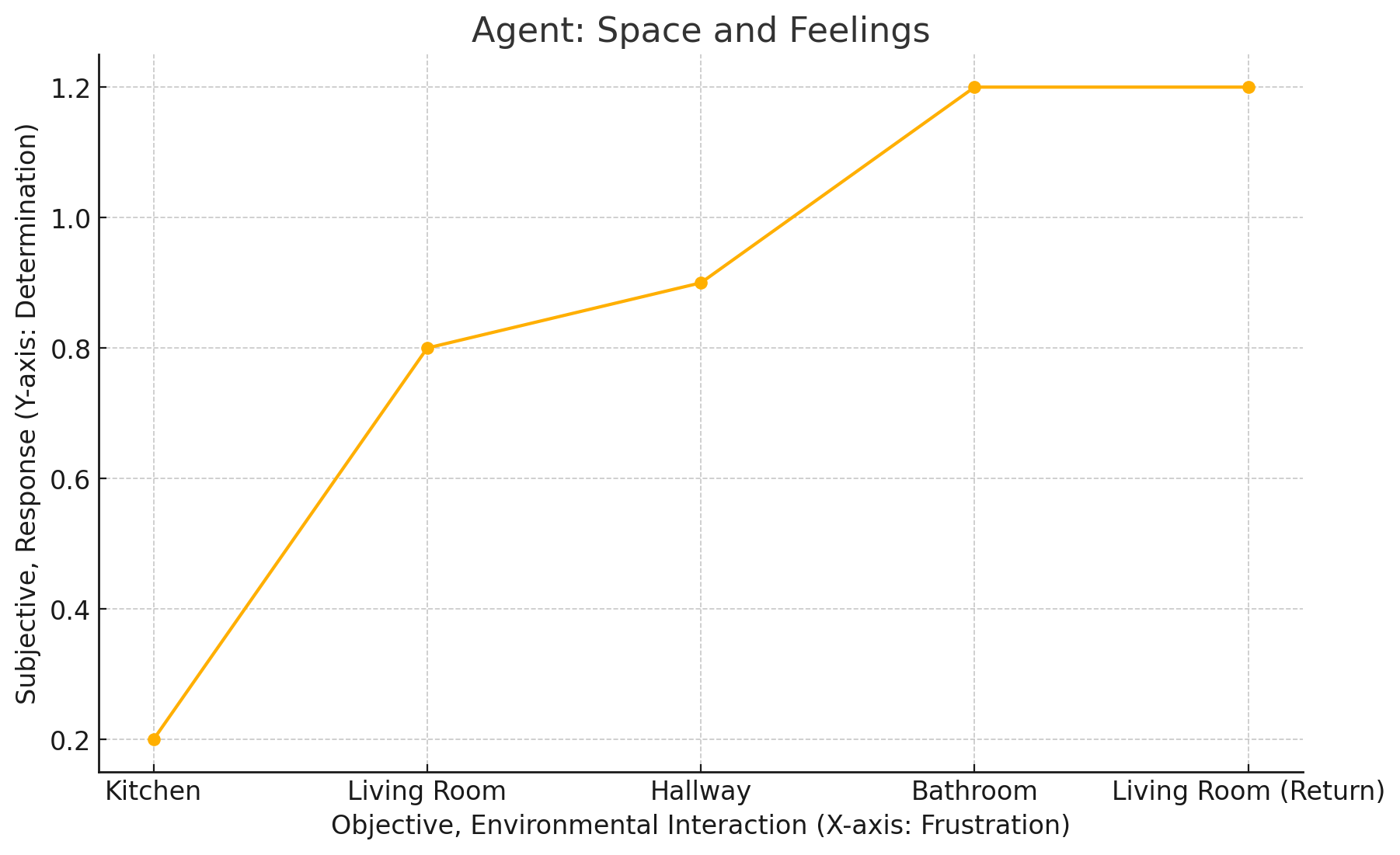

Environment and Emotion

Space (E.g., Rooms) and Agent (E.g., Determination):

Dynamic Bifurcation of Agents’s Subject-Object Axes

This Quadranym Semantic Framework offers a structured yet flexible method for applying orientations, keeping meaning and measurement distinct while supporting context-rich interpretations within the DQM framework. Quadranym units organize concepts into four interrelated facets, providing a structured way to interpret dynamic contexts, spatiotemporal relationships, and orientations within the DQM framework. They enable flexible, context-specific orientation by anchoring meaning through balanced opposites as the context evolves in time.

Subjective Nowness

Complimentary opposite X—Y mode facets of the Agent quadranym:

The subjective element in this representation reveals itself in three distinct ways:

- Subjective/Present (at the Origin):

- The origin (0 on the Y-axis) represents moments where the subject’s attention is fully in the present, focused on immediate actions or tasks (e.g., “Searching Through Clutter”, ” lifting shoes and bags”, or “Opening Bathroom Drawers”).

- Future-Oriented Expectations (+Y):

- Points above the origin capture future-oriented thoughts—moments when the subject anticipates, predicts, or hopes for an outcome (e.g., “Glancing at the Clock,” where there’s worry about time, or “Heading to Hallway,” expecting to find the keys).

- Past Reflections (-Y):

- Points below the origin reflect past-oriented thoughts, showing times when the subject recalls, reflects, or re-evaluates previous actions (e.g., “Remembering Last Night” or “Checking Under Couch Cushions”).

- More Positive (+Y):

- A higher position on the positive Y-axis indicates stronger future orientation. The further up the point, the more the subject’s thoughts are focused on anticipation, expectation, or potential outcomes. These are more sustaining.

- Example: A point at +2 (like “Glancing at Clock”) suggests greater concern or urgency about what’s to come—perhaps feeling pressed for time or intensely focused on a future event.

- More Negative (-Y):

- A lower position on the negative Y-axis reflects deeper engagement with the past, indicating more intense or sustained reflection, recall, or even regret.

- Example: A point at -2 (like “Remembering Last Night”) shows a strong pull toward past events or actions, perhaps due to emotional impact, importance, or the need for re-evaluation of previous actions. These are more sustaining.

This triple presence of the subjective—the present focus, future anticipation, and past reflection—mirrors how thoughts naturally shift between immediate action, memory, and expectation, grounding the analysis in a richly layered perspective. This setup aims to capture the multifaceted nature of subjective experience in real-time. The objective (Keys) is targeted along the temporal movement intersecting past and future as the potential possession in time.

A Slice of Time

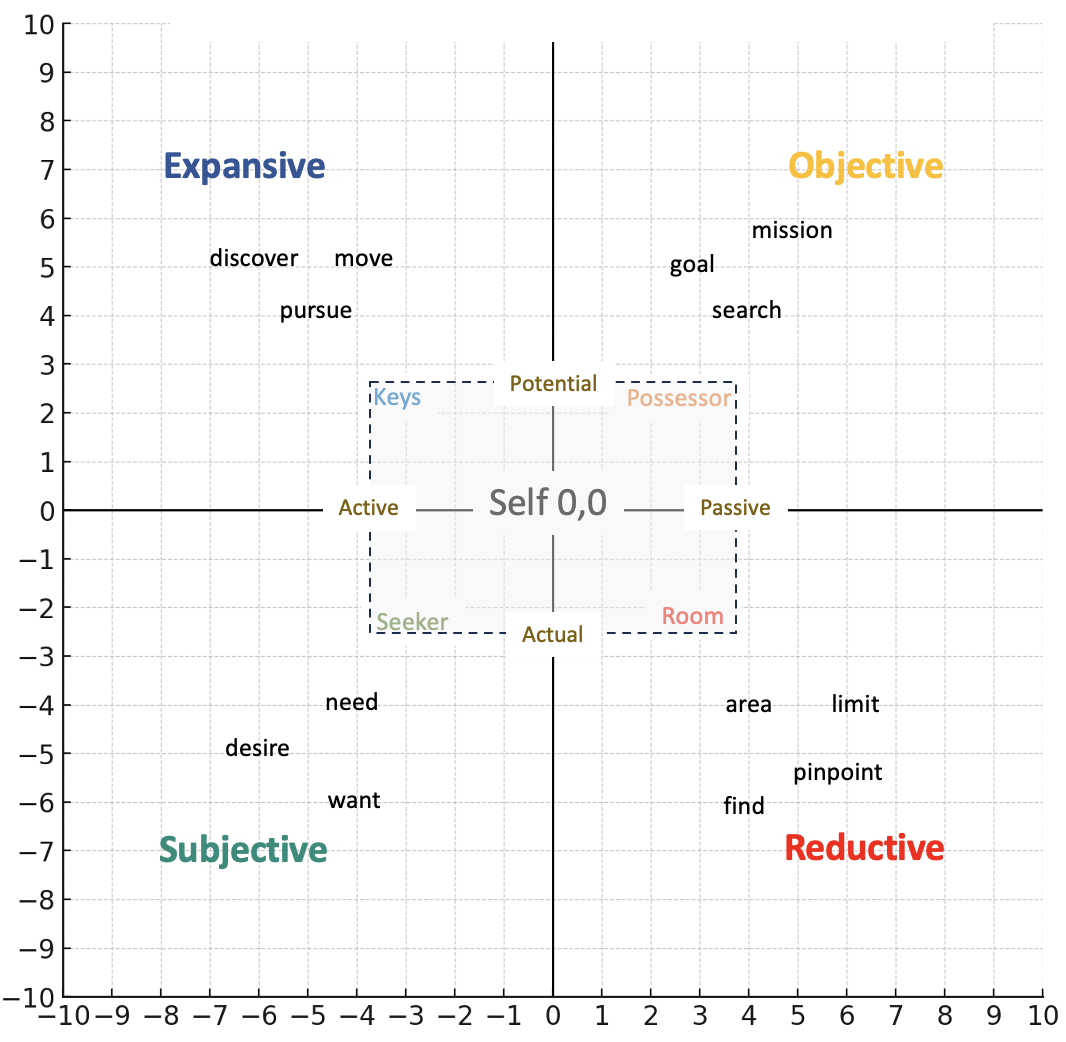

Sarah the Seeker

- Semantics-States:

- Seeker: The origin, anchoring the subjective semantic foundation.

- Possessor: The plot line representing objective possibilities.

- Measures-Modes:

- Keys: Abstract associations along the Y-axis.

- Rooms: Concrete associations along the X-axis.

The “Seeker” above serves as the relevant-subjective anchor (identification opportunity) within the story. As the self, the Seeker grounds the entire script, with the Alpha representation (semantic picture) presented in the chart below as a template throughout each stage of the script.

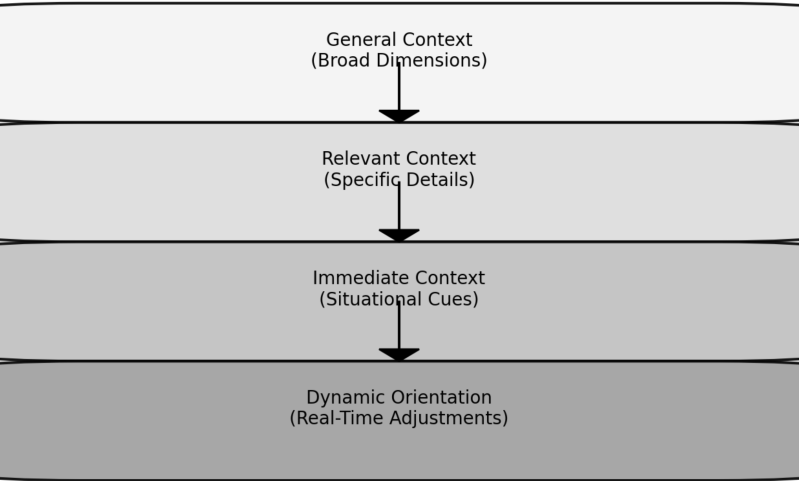

Hierarchical Layers of Orientation

The chart above shows how orientation flows through four layers, guiding meaning from broad goals to real-time adjustments. These layers balance stability with flexibility, shaping how meaning evolves dynamically in the Dynamic Quadranym Model (DQM).

- General Context:

- The top layer anchors meaning with broad dimensions, like Seeker to Possessor in the Keys Story. It establishes the overarching orientation driving the process.

- Relevant Context:

- This layer embeds specific details, such as Keys in the expansive quadrant and Rooms in the reductive quadrant, providing focus within the general orientation.

- Immediate Context:

- Captures situational cues, like searching a counter or transitioning rooms, responding to the specifics of the moment.

- Dynamic Orientation:

- The bottom layer fine-tunes meaning in real time, adjusting to shifts in context, like Sarah encountering new possibilities or obstacles.

Together, these layers allow the DQM to balance broad, stabilizing orientations with adaptive, context-sensitive adjustments, seamlessly connecting big-picture goals to specific actions.

Active Orientation Layers

Feedback Loops (within each quadranym)

Each quadranym operates as a feedback loop, where the active orientation naturally becomes the passive orientation, completing the cycle of meaning. This process isn’t about simple verbs acting on nouns, like find key, but about orientations reaching satisfaction—not in a positive sense, but in achieving completion.

Example: Keys Story:

In Sarah’s search for her keys, several feedback loops drive her actions:

- General Feedback:

- Active = Leave > Passive = House

- The overarching orientation centers on leaving the house. This constant feedback loop provides context for the entire scenario, framing the search itself.

- Active = Leave > Passive = House

- Relevant Feedback:

- Active = Find > Passive = Keys

- Sarah’s immediate orientation is directed toward locating her keys, completing her focus within the general feedback loop.

- Active = Find > Passive = Keys

- Immediate Feedbacks:

- Active = Search Counter > Passive = No Keys → Active = Transition Room > Passive = Search Room.

- These smaller loops guide her real-time actions. Each search completes with either finding the keys or transitioning to the next space, driving the narrative forward.

- Active = Search Counter > Passive = No Keys → Active = Transition Room > Passive = Search Room.

Feedback: The Connective Tissue

Feedback is a core mechanism, seamlessly integrating units, scripts, and layers

Feedback Loops in Action:

- Within Units:

- Active-Actual: Evaluating present engagement.

- Passive-Potential: Assessing progress toward resolution.

- Between Units:

- Transition: Ensuring the action leads to the next step.

- Across Layers:

- Consistency: Aligning actions with overarching goals.

- Temporal Feedback:

- Adjustment: Adapting to changes over time.

- Learning:

- Optimization: Using insights to improve future responses.

By evaluating, adjusting, and linking orientations, feedback enables the Q model to synchronize actions and responses in real time, forming a dynamic framework for fluid interaction and situational adaptability.

Closing the Circuit

An active-passive cycle represents how an orientation transitions from engagement to resolution, completing a meaningful arc. The active phase initiates an action or intent, while the passive phase concludes it, making the moment tangible and salient for the agent. This isn’t about objects being active or passive but about how orientations achieve closure.

The cycle provides the experiences and expectations that guide future actions. These expectations, represented by the passive-potential state, reflect what the agent anticipates based on prior resolutions.

Example: Stepping Out of Bed:

- Active = Step → Passive = Floor

- The act of stepping transitions into the realization of the floor’s stability. This passive phase anchors the moment, allowing the agent to move on to the next orientation.

- The floor itself isn’t passive; it’s the orientation—stepping to stand—that resolves into the passive phase.

Takeaway:

The passive phase completes the arc of meaning, ensuring the moment is experienced fully and recognized as significant. It also sets the foundation for future expectations, providing a passive-potential state that anticipates similar stability in subsequent actions.

The Energy Dynamic:

In the Dynamic Quadranym Model, orientations are both general and specific, with each quadranym reflecting how meaning is shaped in its context. In Sarah’s search for her keys, her active orientation is her role as the seeker—deciding where to look, moving through spaces, and maintaining focus. The passive orientation consists of the resources that sustain her efforts: the arrangement of the rooms, the urgency created by the clock, and even her frustration. These passive elements are not inert; they provide the foundation and fuel for her active engagement. Together, this active-passive energy dynamic ensures her search remains coherent and adaptive, allowing her decisions to flow naturally from the constraints and possibilities of her environment.

Capturing Interpersonal Dynamics

Unlike traditional models that rely on fixed associations or predefined rules, the Dynamic Quadranym Model (DQM) enables AI to “have” knowledge dynamically. By internalizing orientations and contextually adapting them in real-time, the model doesn’t just retrieve information—it actively engages with and aligns knowledge to evolving scenarios. This capacity to absorb and situate knowledge allows DQM to function not as a repository but as an interpreter, shaping understanding as it unfolds.

• The Dynamic Quadranym Model transforms AI’s understanding of meaning, bridging static interpretations and dynamic, real-time adaptability to create systems that respond with human-like nuance.

Final Thoughts: LLMs are powerful tools, and working with them has been an amazing experience due to their brute-force association-crunching capabilities. However, they struggle to create stable general orientations that can adapt while preserving elements like the emotional impact of a book. This limitation fascinates me. In a way, they lack the logarithmic nuance of human analysis, relying instead on a more linear approach to associations. While linear methods can eventually achieve results, they lack the fluidity and adaptive depth of human conversations. There is much more to say and explore on this topic, and I look forward to feedback and future discussions.

By Dane Scalise

One thought on “The Dynamic Quadranym Model (DQM): Integrating Semantic Structure and Responsiveness for a Situating AI”

Comments are closed.